We didn’t really do Gap Years in Worthing. Gap Years were for the beautiful daughters of Kensington millionaires to screw their way through a ski season and then find spiritual redemption in India, or for the double barreled sons of City financiers to dye their already flushed cheeks vermillion in the Africa sun. But due to an administrative error involving a bottle of gin and some incorrectly filed forms, I had to take a year off before Oxford.

The idea of a traditional Gap Year filled me with dread. I had no interest in saving the third world, no wish to find myself. Finally reaching the end of an adolescence whose turbulence would have plucked planes from the sky, I only wanted to be away at university, in a cosy study room, reading Kafka. As it was, my mother put in a telephone call to an old friend, and I was found a job working for my sister’s godmother who was the CEO of a fashion company in Paris.

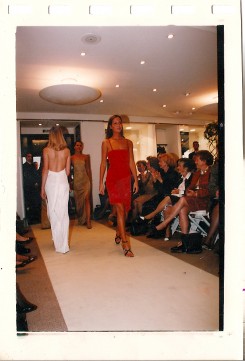

It was perfect – I lived in a penthouse apartment on the Quai d’Orsay, walked over to the office on the Avenue Montaigne every day, stopping for Le Monde and a noisette at the Café de l’Alma on my way. My task at Céline – that’s the name of the label I worked for – which I accepted with great enthusiasm, was to audition models for catwalk shows. I was in eighteen year-old’s heaven.

On one of my first nights in Paris, I was invited by some colleagues at the fashion company to a party in the Bois de Boulogne. It was a fantastic, glamorous bash and I, drunk and star-struck, finally headed home in the early hours. My taxi surged through empty streets until we were within a few minutes of my flat when we suddenly came upon a stationary traffic jam. I got out and walked through the mild August night, and soon saw the cause of the jam. Directly opposite my flat there had been a terrible traffic accident. An ambulance nosed its way between a reluctantly parting sea of cars, policemen stood, looking slightly bewildered, at the mouth of the tunnel that snakes beneath the Place de l’Alma. I skirted the scene and took the elevator up to bed. Remember that crash, though – I’ll come back to it.

At the end of my year in Paris, it was decided that I should have had at least a taste of the traditional Gap Year. Whether it was my new habit of sporting a flambouyantly coloured cravat at my collar, or when, on a visit home to Worthing, I ordered an amaretto instead of my usual pint in the Half Brick, my father decided I needed toughening up. For the final fortnight of my pre-university freedom, I was sent – with my best friend Julian as a reluctant wing-man – to Kenya.

The sense of shock descended when we landed at Jomo Kenyata airport. I had grown used to a certain way of living in Paris – easy, cultivated, luxurious. I still remember very clearly the swarm of mosquitoes that hung in the flickering halogen glow of the baggage hall. “Malaria, dengue fever, Japanese encephalitis” beat a doom-laden tattoo in my head. Where were my monogrammed handkerchiefs? Where was my silver-plated cigarette holder? Where was my shark-skin lounge suit?

Of course nineteen year olds are as resilient as they are malleable. Within a few days I had settled into the life out there and was happily negotiating my way around Nairobi in the back of the Nissan Sunny vans called Matatus that fling themselves along the city’s potholed roads, somewhere between bus, taxi and rollercoaster.

And here I come to the heart of my story. With a few days left to go, Julian and I decided that we’d like to visit Karen Blixen’s place on Lake Naivasha. We’d need to catch a matatu to the Nairobi railway station and then take the Kisumu train northwards. We packed rucksacks for an overnight journey and made our way down to the main road to wait for the next matatu. A black Nissan with tinny music blaring from its speakers pulled up and we were just about to squeeze ourselves into the interior – which already held seven locals on their way to market – when I patted my pocket. I had forgotten my camera.

We had time to spare before our train, and so, with many apologies, we backed out of the matatu and waved it off. Across the entire back window, I remember very clearly, was a sticker – in shiny red green and gold – of Bob Marley. We ran back up to the house, I picked up my camera, and we caught the next matatu into town, having lost no more than five minutes in our detour.

For the sake of narrative tension, I’d like to say here that we felt the windows shake as we drove into town and thought nothing of it, but actually we were blissfully unaware that a car bomb filled with 500 cylinders of TNT had been driven into the secretarial school next to the US Embassy in the centre of town moments before our arrival. Over two hundred people were killed that day – the vast majority Kenyans – and four thousand injured. The embassy was directly opposite the train station. Our matatu pulled over to the side of the road and we walked up towards the plume of smoke that rose from the shattered building where the bomb had exploded.

When we got there, the security forces were already on site. A cordon had been set up and we pushed ourselves to the front. A hundred yards down the road, its nose buried in a ditch, I saw a black Nissan van, all of its windows blown out save the back one, which was held together by the metallic red green and gold sticker of Bob Marley that stretched across it. We went to the bar of the Hilton and got roaringly drunk.

The poet John Oxenham said “life begins at death’s first touch” and I’ve always thought that there was another me, who’d remembered his camera that day, and got into the black matatu. For all I know the people on board escaped unhurt, and anyway there must have been scores of black Nissans in Nairobi with Bob Marley transfers in their back windows. But that day I was aware for the first time of the way that tiny decisions can rule our fate, and the thin line that separates us from death, and the way that our own life as we know it is only one of an almost infinite number of possible lives and deaths that we could have lived.

I said I’d come back to the car crash: it was, of course, Princess Diana who died in the tunnel under the Place de l’Alma that night. Monica Ali’s Untold Story – a better book than the snide critics would have you believe – is the newest in the ranks of counterfactual narratives that pose the great ‘What If?’ around historical events. Her book imagines what would have happened if Henri Paul hadn’t crashed, if Diana had carried on living, just as I did when I patted my pocket, and saved my life.