I was writing an essay on Beckett’s prose and the minimalist composers recently, and something kept nagging at the edge of my consciousness. The thesis of the piece I was working on was that Beckett, like Philip Glass or Steve Reich, uses the interaction of repetition and snatched moments of extraordinary lyricism to convey life as it is lived. Thus in The End, after a long period of repetition, we suddenly have the following passage, which achieves formally what it describes – the sun shines all the brighter for the fog of repetition that it interrupts: ‘I was making my way through the garden. There was that strange light which follows a day of persistent rain, when the sun comes out and the sky clears too late to be of any use. The earth makes a sound as of sighs and the last drops fall from the emptied cloudless sky. A small boy, stretching out his hands and looking up at the blue sky, asked his mother how such a thing was possible. Fuck off, she said.’ Of course, Beckett, resistant to the Romanticism that always sits just behind his work, snatches the moment away from us with that ‘Fuck off’ at the end of the passage.

As I was writing, I kept thinking that there was something I was missing. Someone else employed this very trick, and could be brought into the essay to support the argument. It was only after I had submitted the piece, and was reading Julia Donaldson’s Stick Man to my little boy, bath-squeaky and pyjama-clad on my knee, that I realised it was from a certain type of children’s book. Because of course repetition is a key facet of myth, and our children’s stories have the most direct relationship with the structures of myth. In Stick Man, as in The Odyssey, we have a hero who must go through a series of tribulations on a long and dangerous voyage before being reunited with his family in his tree-Ithaca. The repetitious nature of these trials builds to a crescendo as the text compresses into single-frame signifiers – from the dog who chases him to the swan who uses him to line her nest we move to a tableau of indignities until Stick Man lies, spent and Christ-like prostrate, in the snow. From the repeated refrain – “I’m not an arm! Can nobody see, / I’m Stick Man, I’m Stick Man, I’m Stick Man, that’s me!” – we suddenly move towards a moment of high lyricism when is seems that all is lost: “Stick Man is lonely, Stick Man is lost. / Stick Man is frozen and covered in frost… He can’t hear the bells, or the sweet-singing choir…”

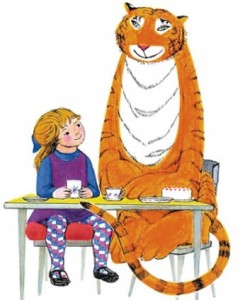

Similarly in Judith Kerr’s The Tiger Who Came to Tea (there’s a wonderful interview with her here) we find the bulk of the story in the repetition of the tiger eating “all the cake” and “all the milk in the milk jug and all the tea in the tea pot”. Only at the end of the tale, when Sophie’s father has appeared and the tiger’s occupation has been lifted, do we come again to a deeply lyrical scene. “So they went out in the dark, and all the street lamps were lit, and all the cars had their lights on, and they walked down the road to a café.” Here the artwork underlines the effect of the language, with the low full moon hanging above the street lamps and and the shop lights illuminating the happy family scene. An orange and black-striped cat appears behind them as a reminder of the return to normality – it is anything but the suave and threatening tiger of earlier in the book.

In one of our favourites, No Matter What by Debi Gliori, the baby kangaroo – Small – asks his non-gender specific parent Large whether he/she would love him under a variety of Kafkaesque transformations (into a bug, bear or crocodile). The answer is repeated each time “I’ll always love you, no matter what”. At the end of the book Small asks “But what about when we’re dead and gone? Would you still love me? Does love go on?” In a gloriously touching scene, with curtains billowing out onto a Van Gogh sky, we find again a moment of lyricsim that interrupts, and is heightened by, the preceding repetition: “Large held small snug as they looked out at the night, at the moon in the dark and the stars shining bright. ‘Small, look at the stars – how they shine and glow, but some of those stars died a long time ago.'”

Whenever my little boy watches The Snowman, with its brilliant David Bowie cameo, he repeats again and again the word “sad”. The lyricism of these children’s stories does have something elegiac about it. The final scene of Michael Rosen’s We’re Going on a Bear Hunt is a good example. It’s a picture of the bear walking lonely by the shore in the light of a full moon and prompts a “poor bear” from my boy who had previously gnawed his knuckles watching the family scamper away from the terrifying beast. But again a scene of (this time purely visual) beauty in a story that draws upon the repetition of a series of trials (which in Deleuze’s terms are “clothed” rather than “naked” repetition). The formal technique whereby repetition is interrupted by lyrical beauty does teach us something about life – how beauty is often heartbreaking, how the world is largely mundane but illuminated by snatched moments of wonder which burn brighter for their briefness. We must savour these moments as we rip them from the dull surrounds of quotidian repetition, hold them close to us as we age, as Bowie/James holds his snowman scarf.