I came to Jamaica with a broken heart. I was twenty – maybe the best time to have your heart broken. The teens are spent lurching from one emotional train wreck to another, but underlying the pain rests the knowledge that things are not yet serious, that your heart is not yet quite en jeu. At university things changed – relationships suddenly developed a certain seriousness. People went on to get married from here, we thought, as we flirted and dated and fucked.

Hearts only get broken once. The muscle cells of the heart do not regenerate. Each further assault after the first break merely serves to continue the destruction of the organ. Later-life events like divorce and bankruptcy and the death of a child are all tragedies that serve to confirm that fatal original blow.

When my godmother heard about my misfortune, she sent me a ticket to Jamaica. It was early September – we would go for two weeks, stay in a villa that an old friend of hers owned on the northeast of the island. I had been in bed for two weeks reading Rimbaud and Hölderlin. I needed the change of scene.

I arrived in Montego Bay the night before my godmother and checked into a hotel next to the airport. I sat on the balcony and watched the sun go down, sipping at a Red Stripe and feeling a delicious sense of loneliness. I was alone on an island miles away from the world that had so wounded me. Crickets rose their voices to the fiery evening sky. Night birds called out as they flew in swift shadows down to the seashore.

My godmother landed early the next day and we made our way along the rutted track that led to Ocho Rios in an open-top jeep driven by a beaming Rasta called Henry. We passed coves of white sand overlooked by nodding palms, boats pulled up almost to the road filled with fishing nets and harpoon guns. We stopped at Noel Coward’s house – Firefly. It was white and modernist and rather unimpressive. I ate conch from the shell. We finally came to the villa that was perched on a hillside overlooking the sea. We unpacked and strolled down the steep slope for a swim.

The next day we set out to visit a friend of my godmother, Patrice Wymore. She lived on the coconut plantation that she and her husband, Errol Flynn, had bought in the 1950s, just as his career was beginning to fade. We rented a car in Port Antonio and drove under the shadow of the Blue Mountains until we came to a headland where the road described a long curve between clumps of scrub and acacia trees. Sad-looking horses grazed on dusty grass. There was a huge pile of coconut husks by the side of the road. The flesh in some was still rotting and a black shimmer of flies rose up as we passed. We turned off the road and drove up the hill until we came to a lightening-struck tree with a sign hanging from it that read Mulholland Farm.

The house was surrounded by lush trees, swamped with bougainvillea. It had once been white, but had come to take on the colour of the land, dusty and sun-bleached. Pat was waiting for us as we drew up outside.

Errol and Pat Flynn lived at Mulholland Farm throughout the 1950s. The house, perched above the coconut plantation, looked down on a forest of palm trees, and was built to provide an escape from Errol’s dissolute Hollywood existence. He and Pat rode across the surrounding countryside on horses, rowed down rapid-furrowed rivers before drinking sundowners on the beach, lived like young honeymooners even though he was heading towards fifty, and his liver (an organ whose cells are thankfully extremely regenerative) was much older. Flynn’s wild lifestyle wasn’t entirely left behind in LA. He once loosed a crocodile in the centre of Port Antonio market; Pat told me that rumours of him driving into their swimming pool smoking a cigar weren’t true. “He didn’t smoke cigars,” she said.

The swimming pool now stands empty. Errol Flynn died in 1959, aged 50. Pat has lived on the estate ever since. The rooms are dark and full of dustsheet-covered furniture. Birds squabble in the roof. Dust blows in waves across the floor.

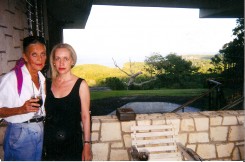

Pat poured us drinks and we sat overlooking the concrete lacuna of the swimming pool, watching the sun move slowly across the plantation below. Pat told us stories of living at the farm with Errol. Her eyes misted and she paused occasionally with a distant smile on her lips as she reminisced. When my godmother told her of my own recent romantic misfortune, Pat placed her hand on mine and fixed me with a gaze of extraordinary warmth. “Love comes again,” she said, and she led me by the hand down to a spot where we could see the sea surging up the mouth of a river, bright birds in the trees, mangoes hanging heavily from dark-leafed bushes. “Errol and I used to come and stand here,” she said as the wind whipped around us. “I still come down here every night and look at the river.” A closeness built between us in the thick Caribbean air. We drank some more and then it was time to go.

I found out afterwards that we had visited Pat on the first anniversary of her daughter’s death. Arnella Flynn, a one-time model in Europe, was found by plantation workers dead in her bed after a short life of drug abuse. She was Errol and Pat’s only child. I look at the picture of Pat, hand on hip, smiling, and I try to find that pain, try to locate the sadness she must have felt. And I wonder whether it was her warmth, her kindness despite the crushing weight of her loss, that caused my solipsistic self-pity to evaporate as we stood looking down over the river that evening.