On Remembrance Sunday, 2012, I preached my first ever sermon on a wintry Oxford evening at St. John’s College Chapel. Here it is.

“The wolf shall lie down with the lamb, the leopard shall lie down with the kid… The nursing child shall play over the hole of the asp, and the weaned child shall put its hand on the adder’s den.” Isaiah prophesying peace. Images firmly embedded in our cultural consciousness, a common shorthand for tranquility. Perhaps – dare I say it – clichéd images. Certainly used more in irony than otherwise in these battle-scared times. After the nightmare of the twentieth century, the violence that continues to define the twenty-first, it’s hard not to feel that we’re further than ever from Isaiah’s pacific vision, that this is one person’s dream (or rather several, given that it’s likely that the Book was written by a number of different Isaiahs), conjured up against a backdrop of the destruction of Jerusalem, the sacking of Tyre, the muscle-flexing of belligerent Babylon, the Assyrian wars. The Peaceable Kingdom acts as a counterpoint to the violent visions to come – the Isaiah Apocalypse in Chapter 24:

“Behold, the LORD maketh the earth empty, And maketh it waste, And turneth it upside down, And scattereth abroad the inhabitants thereof. The land shall become utterly emptied and utterly spoiled.”

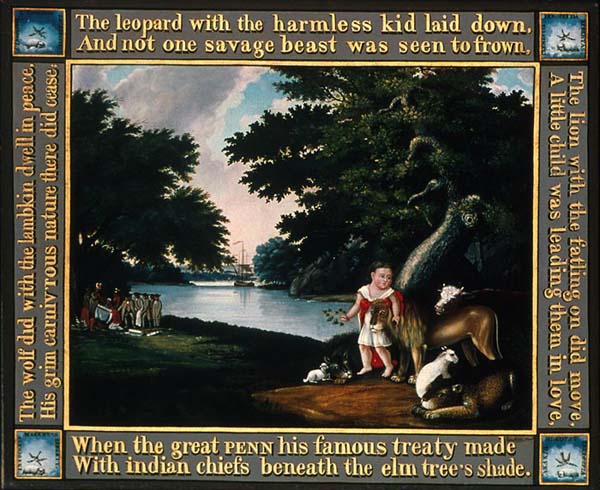

In 1813, a Quaker minister, Edward Hicks, took up painting as a way of financing his itinerant preaching in poor, rural Pennsylvania. He painted one scene repeatedly, Isaiah’s ‘Peaceable Kingdom’: on bedheads, on tavern signs, on carriages, on farm machinery. Soon his painting career had become so lucrative that it caused frictions with his fellow brethren, and he gave up for several years, trying to make it as a farmer. In 1816, bankrupt, with his wife expecting their fifth child, he took up the brush again. He painted 61 versions of the vision from Isaiah in all, each of them an attempt to capture the Quaker doctrine of ‘Inward Light’ – the belief that there is something divine within man, a reflection of what John calls “the true light, which lighteth every man that cometh into the world.” He gave his animals human characteristics, one of which was this sense of radiating some ethereal, Christ-like goodness.

Often the paintings would vary very little, a Rousseau-ish lion posed slightly differently in one picture, the cherub-like children sprawled first one way, then another. Over his lifetime, the paintings became darker, the anthropomorphized animals grew white whiskers, the symbol of a lightning-divided tree appears, representing not only the split within the Quaker Church that occurred at this point, but some deeper, more elemental divide in Man, calling to mind the other tree that caused us to leave that original peaceable kingdom.

Even so, the paintings are essentially the same, each one attempting to capture more accurately, more atmospherically, Isaiah’s irenic prophecy. There’s something traumatised in this repetition, a compulsion that sees Hicks reaching again and again for this vision, for a dream of peace that he knows is not achievable, that he realizes is mythical, utopian, jarring with the violent world he sees around him still reeling from the revolutions of the late eighteenth century, the bloody Napoleonic wars.

It is, perhaps, the quintessential meme, this idea of a lost Eden, a paradise to which we all long to return. We find it in the representation of the Golden Summer of 1914 in the work of the First World War poets – a blissful, sun-kissed time before the war cast all into darkness. We find it in Sassoon’s ‘Idyll’:

“In the grey summer garden I shall find you

With day-break and the morning hills behind you.

There will be rain-wet roses; stir of wings;

And down the wood a thrush that wakes and sings.

Not from the past you’ll come, but from that deep

Where beauty murmurs to the soul asleep.”

We find it in later war poetry, that looks back to peacetime with an aching wistfulness. In Frank Thompson’s ‘Polliciti Meliora’:

“As one who, gazing at a vista

Of beauty, sees the clouds close in,

And turns his back in sorrow, hearing

The thunder-claps begin.

So we, whose life was all before us,

Our hearts with sunlight filled,

Left in the hills our books and flowers,

Descended, and were killed.”

In 1941 Keith Douglas, not too far from where we are now, wrote ‘Canoe’, about punting on the Iffley.

“I cannot stand aghast

at whatever doom hovers in the background:

while grass and buildings and the somnolent river,

who know they are allowed to last forever,

exchange between them the whole subdued sound

of this hot time.”

There is something within us, something wounded, that calls out for this peaceable kingdom, that drives us – even though the broad sweep of human history insists otherwise – to seek peace in a world shattered by violence.

“Peace I leave with you, my peace I give to you,” says Jesus is his Last Discourse, the farewell speech he makes to his disciples at the Last Supper. It’s Remembrance Sunday today, a time to call to mind those dead in war, the hecatomb of bodies that we see as we stand, like Walter Benjamin’s Angel of History, and look back at the ravaged years, counting on our fingers the great battles and their great victims. This is some tarnished peace we’ve been left, whatever peace Christ gave us seems barely worth the name. The historian Will Durant claims to have identified only 29 years in all of human history when a war wasn’t being fought by someone, somewhere. Knowing humanity, one suspects that with a little more work he might fill in those missing years.

But it’s the next line in the Last Discourse that interests me. “I do not give to you as the world gives.” I don’t know about you, but the first time I read this passage, I rather passed over these words, put them down as one of those gnomic statements that, because of bad translation or a lost reference somewhere just doesn’t make sense. But then I looked at it again. I was reminded of a passage in Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s The Cost of Discipleship. He takes the phrase from Matthew – “Blessed are the peacemakers” – and uses it to examine the idea of peace in the Bible. He points out that “peacemakers” is a poor translation of the Greek ei-ré-no-poi-os. A better translation, he says, would be peace-receivers, although even this isn’t quite right. The Greek wants both meanings. Bonhoeffer ends up discarding the attempted translation altogether and calling instead on St Francis of Assisi: ‘Lord make me an instrument of thy peace.’ We are not the agents here.

‘My peace I give to you. I do not give to you as the world gives.’ We are being presented with two distinct forms of peace here. The peace that “the world gives,” the peace that we, by attempting to build bridges with other humans, might achieve, the peace in which we act as agents; and the peace that Christ gives us, where we are his instruments. And in this latter, I believe, we may look back to Isaiah’s eschatological vision, call up the picture of the wolf and the lamb, the child and the adder’s den. This is end-time peace, perfect peace, something our world-peace may only hint at. Christ is not giving us the fragile, circumscribed peace that we know, briefly, in this violent world. Instead, Jesus is saying here that there is another, higher peace, something only achievable through him, through loving him and keeping his word. It is not that the way we act on earth doesn’t matter, rather that those fleeting, sun-kissed moments of peace that we have here on earth, the glittering visions of Edward Hicks, are pale imitations, shadowy intimations of the peace to come.

This, I believe, is why Christ’s teachings, the Bible itself, operate in the allegorical mode. Why, perhaps, all of the greatest literature has some element of allegory about it. We need ideals, and here we’re given an ideal of peace, a Platonic ideal which at once highlights the imperfection of our earthly attempts, but also gives us something to strive towards, to hold up against the darkness. Allegory is the vehicle in which we approach the non-material realities that cluster beneath the dome of concepts like faith and belief. Allegory allows us – some of us, I guess – to bypass the cynical rational mind. There are things within the deep heart’s core that we cannot confront head-on, for they will blind us. We must look for them in the reflected waters of allegory.

Dear Alex,

You are disturbed by the undergraduate of the Moscow Linguistic University. First of all I would like to express my admiration to your novel “This Bleeding City”. It impressed me greatly to such an extent so I’m writing the thesis according to it. I study the concept of “the personal internal speech” and I make a supposition that in a novel a narrator and the main character may coincide, finding confirmation in your novel. Thereby, I would like to ask you some questions.

1. To what extent would you call this nove autobiographical?

2. Whether are there real prototypes of the main characters of the novel, such as Vero, Henry, Joe, etc.?

3. What works of modern and classical writers had influenced on your style?

I know that you were in Russia recently, but, unfortunately, I found out about it too late. I would be very grateful to you if you could spare me some time. It would help me with my research.

I wish you further creative success.

I am looking forward to your response.

Yours faithfully,

Annastasia.

Dear Annastasia –

Sorry it has taken me so long to reply. Here are my answers to your questions:

1) It is not at all autobiographical. It is, rather, a combination of the experiences of many people I spoke to within the City of London during the financial crash. I think journalists and reviewers are always keen to believe that something is a roman à clef. I believe greater truths come from fiction.

2) No – these are people from my imagination. I guess Vero is, to an extent, modelled on my brother’s ex-fiancé. He was rather mean to her and so I gave her her revenge by making Vero a cold, hard, calculating woman.

3) F Scott Fitzgerald is the obvious influence. Charlie Wales is named after a character in his short story ‘Return to Babylon.’ Otherwise Bret Easton Ellis, Jay McInerney and Jennifer Egan were all influences.

Hope this helps! Good luck with your work and sorry again it took me so long to reply.

Best,

Alex.

Dear Alex,

I want to report that I have defended the thesis successfully. Many thanks for your help. It seems, I advertized your novel among members of the commission. They’re going to read it soon.

Best wishes,

Annastasia.